Olivia Muenter on “Little One,” Selfhood, and Everyday Cults

Olivia Muenter’s novel, Little One, follows Catharine, a woman who was raised in a cult led by her own father until she leaves everything and everyone she knows behind. From there, she must rely on free, public resources to learn how to be a person in society as an adult. Now, about a decade after leaving, Catharine has gained a sense of control over her new life – that is, until she receives an email from a journalist asking questions about her upbringing. When Catharine discovers the charming journalist has spoken with someone from her buried past, she must decide whether she wants to continue running from the life she escaped or come forward and face it head-on.

In this conversation, I speak with Olivia Muenter about Little One, and the process of writing about control – specifically how it operates through cults, diet culture, and systems that reward obedience, as well as what it means to leave those values and structures behind. Through reflecting on selfhood, discipline, and the risk of choosing what feels true over what is acceptable, Muenter offers insight not only into the novel but also into the emotional realities many readers will recognize either in their own lives or the world around them.

Lex: What sparked this idea for the project?

Olivia: I first started writing this book with no idea whatsoever in mind. I just thought of a sentence that would be interesting for the first sentence of a novel, and it stuck with me for a couple years. [Throughout those years,] I don't even think I was like ‘I'm gonna start writing a novel.’ One morning, I was just at my desk early, and I opened a Google Doc, and I just started. I quickly realized that I really liked the idea of writing about a woman who had grown up in a really insulated community. And then it grew from there. But it started with almost nothing.

Lex: Interesting. Do you remember what that first sentence was?

Olivia: Yes, it's no longer in the book, but the sentence was, ‘When the plane went down, I was thinking about donuts.’ And I've talked about this before on my podcast, but I thought of it when I was on a plane for work one time. I was like, ‘oh, that would be interesting, because, like, why is the plane going down, and why would you be thinking about donuts?’ Sometimes you just need that little spark of, like, ‘that would be interesting,’ and that's all it took.

Lex: In the novel, Catharine mentions how there are so many cult documentaries and podcasts in modern entertainment. She also brings up her fear of becoming another story for entertainment. What kind of stories about cults did you want to respond to, complicate, or move away from?

Olivia: I [became] more interested in this juxtaposition of our cultural fascination with cults, and everyone going wild over, the next Netflix documentary. As we watch them, we kind of think, ‘Oh, that could never be us.’ Then we leave the room, where we’re watching TV, and we go into these other sorts of little cults in our life, like SoulCycle and fashion trends. Although [they] are not harmful in the same ways as an actual cult is, of course, there is a very similar line of thinking, and so I really wanted to call out those parallels. Also, the idea that we think we're untouchable when it comes to being a part of one of these communities, but we are so susceptible to it. Like diet culture for instance, so many others of these little pockets of intense communities that exist.

Lex: How did you approach writing a character who had to learn how to be a person in society as an adult?

Olivia: This was an interesting part of the writing process, because those years aren’t on the page. We see Catharine growing up, and then we see her as an adult. And there’s a solid decade of time where we’re not actually seeing what’s going on. But I think the thing that Catharine has in common with her father, among a few things, is that she’s very adaptable and very smart. I think a lot of the reason why cults are successful is because they thrive on this idea of seeing what everyone else around you is doing and copying it. That’s kind of what I imagine Catharine would do in the world: observe as much as possible and then try to assimilate, and to control as much as possible as well. It was a challenge trying to illustrate how she transitioned out of it without having those years on the page.

Lex: This leads to my next question. What made you decide to not show that transition in the novel, but just discuss it in passing?

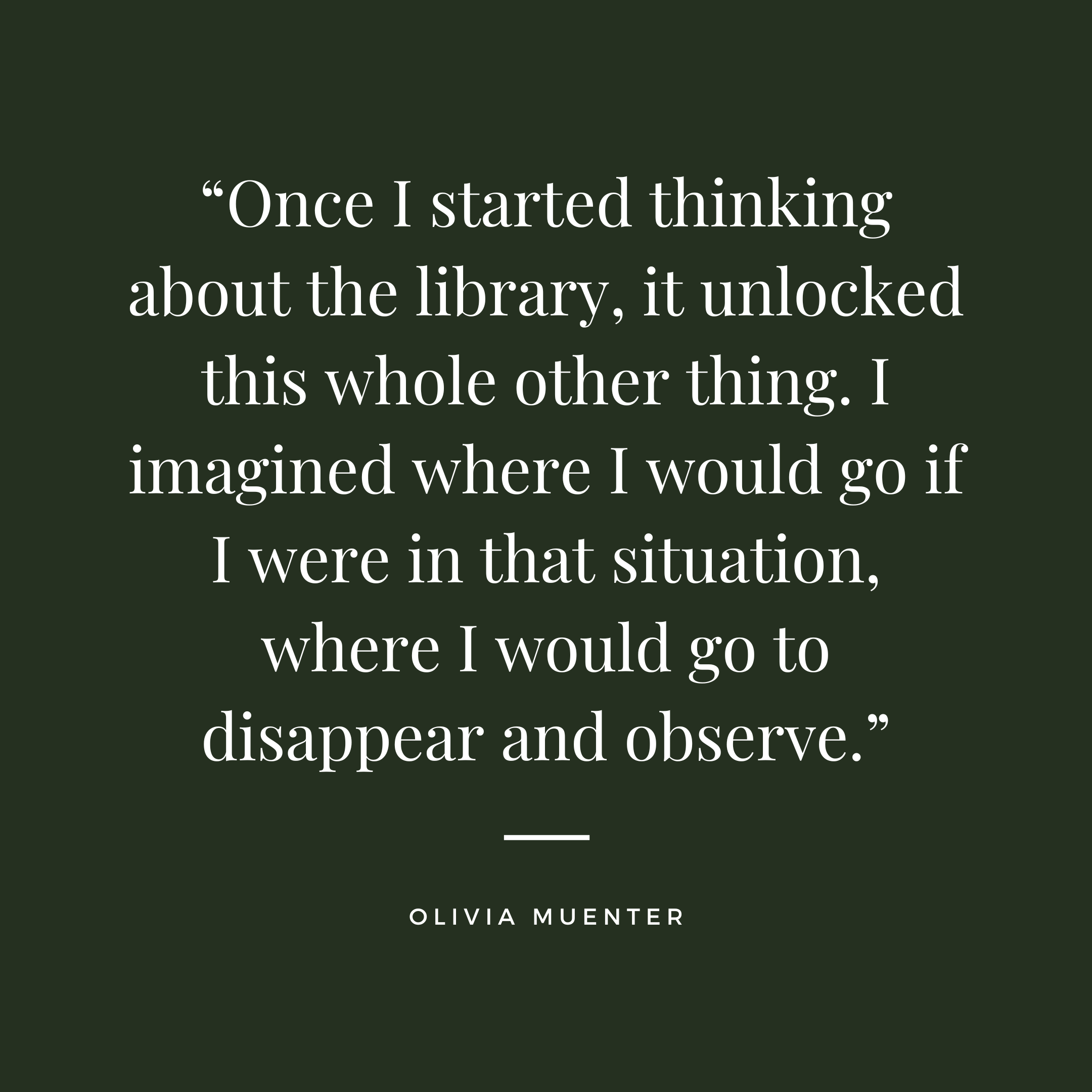

Olivia: It was just the way that I wrote the story. I knew there was going to be this ten-year gap, but the stuff about the library came in very late. One of the things my editor and I talked about was that there were still, at certain points in certain drafts, a lot of questions about how exactly she survived. At some point, there were many more details about what exactly happened when she first got to the city, and we took those out. But I thought the library was this interesting example of a space that’s very free. You can just go in, you don’t have to buy anything, you’re surrounded by knowledge, there are classes, social interactions, technology, which are things that Catharine hadn’t necessarily had access to. Once I started thinking about the library, it unlocked this whole other thing. I imagined where I would go if I were in that situation, where I would go to disappear and observe. That’s how Catharine moves through the world by observing people very intensely, and the library supported that trait.

Lex: The scenes of Catharine as a child, during her time in the cult, were so intense. Difficult, even. For example, the scene of her father punishing her with the bowls filled with feces. It was all very well executed. My question is: how did you get into the mindset of writing such intense scenes of control and brainwashing?

Olivia: Thank you. They’re not intended to be easy scenes, so I’m kind of glad they were difficult. They’re supposed to be a little painful, and they were painful to write, especially the ones later that are more about weight. Those came from a personal place, as I’m sure many women can relate to in different ways. A lot of the cult material came from my own emotional experience with control and controlling my eating. That’s really what informed it. In a way, it was harder because it felt close to me, but I was also thinking so much about the emotional reality that I could distance myself a little from the abuse itself. While it’s a situation I’ve never been through literally, the emotional experience is very real for me, and I’m sure for other people as well.

Lex: Did you do any self-care throughout writing those scenes or the project as a whole?

Olivia: I’ve been in therapy for a very long time, and I think it’s only because of that that I’m able to write. In many ways, writing this was self-care, such as illustrating the darkest places I’ve been or thoughts I’ve had about myself and putting them in a different context. It was healing and cathartic in a way I didn’t fully understand until I was on the other side of it. Even the most painful scenes felt true to me, and that was the goal. It felt freeing.

Lex: I love that. Why did you choose to tell the story by moving back and forth between past and present?

Olivia: At first, it just sounded interesting, but as I got deeper into the story, I realized so much of the heart of the narrative is about what we learn about ourselves as children and how it carries through, and what we have to do to unlearn those things.The question of whether we can really let go of them felt central. In that context, the two-timeline format made perfect sense. My hope is that when you see little Catharine and adult Catharine, you understand how someone gets from point A to point B.

Lex: Totally. Sometimes switching timelines can feel risky, but here it made everything click. Speaking of Catharine, she is such a phenomenal character: complex, strong, smart. How did you approach writing her trauma without letting it define her?

Olivia: I wanted Catharine to reflect something I think many people who’ve experienced trauma feel, which is that you can see everything around you clearly, including the darkness underneath things. You’re smart and strong, but those experiences still affect you. [Catharine’s] strong, but she’s also someone who was raised in a particular way. I wanted both sides to be evident. You can understand the world deeply and still be touched by it.

Lex: What do you hope readers gain from this novel?

Olivia: I want people to pause and reflect on their own lives. When you choose something different from what everyone around you is doing, there’s real risk, but also freedom. The only way to truly know yourself is to make decisions outside those systems, not because they’re acceptable, but because they feel true. The book is about what you gain by belonging to systems that reward conformity, what you lose when you leave them, and what you gain when you choose something honest and healthy for yourself.

Lex: You’ve talked about Catharine restricting her eating as a form of control. Did you want to speak more about the themes of eating disorders or control?

Olivia: The cult I’ve been part of my entire life is diet culture, and the obsession with women being small, disciplined, and self-controlled. This book is a parallel to that experience. I hope it makes people think about who benefits from the thinness being required of us. It benefits other systems, not us, and it’s a distraction from more important things. I hope people step back and look at diet culture differently.

Lex: That really resonates. Diet culture feels so prevalent even though there is some visible online engagement with ‘body positivity.’

Olivia: The narrative gets repackaged every time women push back. The book asks whether we’re participating in the same systems repeatedly while telling ourselves it’s different.

Lex: Lastly, what’s next for you?

Olivia: I’m going on tour for this book and coming to LA for the first time to visit Sunny’s Bookshop. I’m also working on another novel, which is very different, but still suspenseful, with a romance element. I’m excited to share more soon.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Lex Garcia Nix / Writer

Lex Garcia Nix is a first-generation college graduate and community college alumna, who teaches at the community college level and is a contributing writer for Sunny’s Journal and Press. She earned her MFA from Antioch University, Los Angeles and has further honed her craft at VONA, Tin House, StoryStudio, and The Community of Writers where she was a recipient of The Ancinas Scholarship. She was recently named a 2026 Periplus Fellow. Lex lives in SoCal and is currently working on a coming-of-age novel.

Read More